I’ve visited Cyprus many times, staying at my sister’s holiday home in nearby Paralimni. Being so close to the legendary ghost city of Varosha, yet unable to visit or even see it behind the military barricades, was always a source of frustration and fascination for me. It was a ‘Forbidden Zone’ just down the road.

For 46 years, that was the story: a glamorous resort frozen in 1974, sealed off and left to rot. But recently, the story changed. In 2020, Varosha was suddenly, controversially reopened—not for residents, but as a surreal tourist attraction. My research focused on this strange new ‘zombie’ state: a place where you can now buy an ice cream and ride a bike past the bombed-out ruins of 1974 hotels.

Where is Varosha?

Varosha was a suburb of the city of Famagusta, located on the east coast of Cyprus. Its most valuable feature was its stunning coastline, a stretch of golden sand that made it a prime location for tourism. It was completely fenced off after it was abandoned in 1974 and entry strictly controlled by the Turkish military.

Varosha is part of the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a state recognised only by Turkey. It is 5 km (3.1 miles) from Deryneia, the nearest Greek Cypriot town. The nearest border crossing is also at Deryneia.

The History of Varosha

The story of Varosha begins long before it became a glamorous tourist hotspot. It’s part of the city of Famagusta which has stood on the eastern coast of Cyprus for centuries, having a storied history as a fortified medieval port city. It was once one of the richest and most important trading centres in the Mediterranean. During the Venetian period in the 14th and 15th centuries, massive walls were built around the city to defend it against Ottoman attacks and Famagusta flourished as a hub of commerce, culture and maritime trade. Even under Ottoman rule and later British administration, the surrounding areas retained a mix of Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, both shaping the region’s culture and economy.

Varosha, originally a modest coastal neighbourhood just outside the old city walls, began as a quiet fishing and farming village. Its long, sandy beaches and proximity to Famagusta made it an appealing spot for summer retreats and over time, small guesthouses and seaside cafés started to appear.

Cyprus came under British administration in 1878 as part of an agreement with the Ottoman Empire and in 1914, when the Ottomans joined World War I on the side of Germany, Britain formally annexed the island. In 1925, Cyprus was declared a Crown Colony, giving Britain full control over its governance. Varosha grew gradually in the first half of the 20th century, benefiting from Cyprus’s increasing accessibility under British rule and the rising popularity of Mediterranean travel among Europeans. Rising nationalist movements throughout the 1950s led to Cyprus gaining independence in 1960 as a republic.

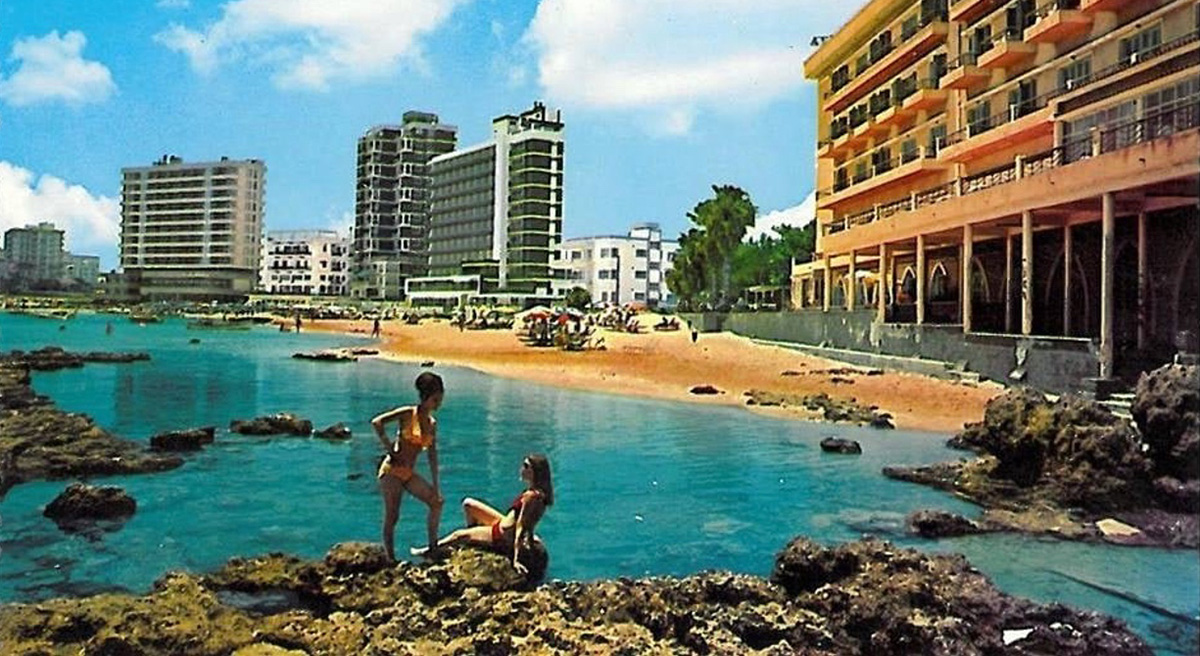

Following independence, Varosha began to transform into something entirely new. Investors and entrepreneurs recognised the potential of its beaches and mild climate. Ambitious construction projects began to shape a modern Mediterranean resort. Hotels, apartment blocks and commercial buildings reshaped the coastline. What had once been a sleepy village became a vibrant seaside resort.

In the early 1970s, Varosha was the epitome of Mediterranean glamour. Its pristine beaches, luxurious hotels and vibrant nightlife made it a top destination for international jet-setters. Among the most frequent visitors were Hollywood legends Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. The couple often stayed at the Argo Hotel, a favourite among celebrities. Brigitte Bardot, the French actress, was another regular. Italian actress Sophia Loren owned property in the area. American actress Raquel Welch was also a frequent guest.

Varosha’s main thoroughfare, John F. Kennedy Avenue, was lined with high-rise hotels like the King George and Grecian, offering amazing views of the Mediterranean. Leonidas Street, the city’s shopping and entertainment hub, had chic boutiques, cafés and nightclubs. This blend of luxury and celebrity earned Varosha the nickname of the Saint-Tropez of Cyprus.

Economically, Varosha was a powerhouse. With 45 hotels and more than 10,000 tourist beds, it accounted for over half of Cyprus’s entire tourism revenue. The streets were filled with bustling cafes, open-air markets, cinemas and nightlife venues. Its residents, who were mostly Greek Cypriots, thrived because of the influx of international visitors.

Why was it Abandoned?

By the early 1970s, Cyprus was caught in the middle of regional politics. The island’s Greek Cypriot majority had long harboured aspirations of Enosis, or union with Greece. The Turkish Cypriot minority were against any merger with Greece, fearing for their own rights and security. Meanwhile, Greece itself was under the grip of a military dictatorship. The Greek junta, which had seized power in 1967, was nationalist, authoritarian and obsessed with expanding Greece’s influence in the region.

The Cypriot president, Archbishop Makarios III, attempted to balance these competing pressures, pursuing independence while resisting calls for Enosis that risked destabilising the fragile coexistence of Greek and Turkish Cypriots. This delicate balance proved increasingly untenable.

On 15 July 1974, the Greek junta orchestrated a coup in Nicosia, overthrowing Makarios and installing a puppet government led by Nikos Sampson, a fervent supporter of Enosis. The move was intended to force the island into union with Greece but it instead ignited a political and military crisis. For the Turkish Cypriots, the coup represented an existential threat, heightening fears of violence and displacement. Turkey launched an invasion, citing provisions laid out in the agreement which gave Cyprus its independence.

The Turkish army advanced through Northern Cyprus and entered Famagusta. The residents of Varosha were overwhelmingly Greek Cypriot and they began to flee in panic. Families abandoned their homes, businesses and all personal belongings, believing they would return once the fighting subsided.

The flight from Varosha was sudden and chaotic. Streets that had once been alive with tourists, beachgoers and bustling markets were abandoned almost overnight. When Turkish forces reached the city, they quickly cordoned it off with barbed wire and declared it a military zone, sealing off Varosha indefinitely. Things remained exactly as they were in Summer 1974.

Over the decades, Varosha has remained a symbol of a frozen conflict. UN Security Council Resolution 550, passed in 1984, affirms that the city can only be resettled by its original inhabitants, condemning any attempt to alter its status. With no political settlement ever achieved, the once-thriving resort began to decay.

What is Varosha like now?

Today, Varosha exists in a strange, uneasy in-between. It’s part ghost town and part tourist curiosity. For 46 years, it was a true time capsule of 1974. Empty high-rises, hotels and apartments stood frozen, gutted by looters and slowly reclaimed by nature. Trees sprouted through floors and roofs, wild plants crept up stairwells and the once-bustling streets were silent except for the cries of seabirds. On its golden beaches, endangered sea turtles made their nests, adding a surreal layer of life to the otherwise abandoned resort.

In October 2020, Turkish Cypriot authorities unilaterally reopened a small section of Varosha’s beachfront to the public. The move was widely condemned internationally as a violation of UN resolutions, but it marked the first time in nearly half a century that civilians could legally set foot in this part of the city. Since then, more streets have been cleared and opened, creating a controlled experience that blends eerie abandonment with tourism.

Varosha has since become a magnet for dark tourism. Visitors can rent bicycles and e-scooters to glide along designated routes, passing crumbling hotels with bullet-scarred facades, empty shops and abandoned apartments frozen in mid-life. Some Turkish Cypriot entrepreneurs have opened cafés along the beachfront, serving coffee and snacks to tourists while the skeletal towers of Varosha loom behind them. Street signs, murals and remnants of old businesses hint at a vibrant life that ended abruptly, giving the place a cinematic, almost post-apocalyptic feel.

Despite the controversy, there have been some limited positives for Greek Cypriots. Former property owners have been able to pursue claims and compensation through international courts, including the European Court of Human Rights. Some have received financial restitution for their lost properties. The ongoing global attention on Varosha has also kept the issue alive in diplomatic discussions, giving Greek Cypriots a platform to assert their property rights and maintain pressure on negotiations. Additionally, some former residents and their descendants can now visit the perimeter of the resort and nearby beaches, offering a bittersweet connection to their abandoned homes.

The future of Varosha remains deeply uncertain. While some Turkish Cypriot entrepreneurs have reportedly purchased old hotels with plans to renovate them, any transformation is politically fraught. The international community continues to consider the reopening illegal and the city remains a symbolic battleground.

For me, looking across the buffer zone from Paralimni all those years, Varosha was always a place of silence and mystery. To see it now, re-opened as a tourist attraction with bike rental stations, feels incredibly surreal. It is no longer just a ghost town; it is a living museum of 1974.

While I haven’t crossed the checkpoint myself, I found this excellent video by Kojanik. It gives a brilliant first-person perspective of cycling through the ghost city, showing just how accessible and unsettling the ruins are today.