Scott’s Hut, located on the desolate shores of Antarctica, is more than just a hut, it’s the world’s most perfectly preserved time capsule.

For me, as someone with an interest in abandoned places, the fascination isn’t the history of the race to the South Pole, but the sheer, haunting reality of the preservation. I researched the ultimate frozen ghost town—a place where food, clothes, and tools remain exactly as they were in 1912. This is the story of that time capsule, and what its contents reveal about the courage and tragedy of the men who never returned.

Where is Scott’s Hut?

Scott’s Hut is located at Cape Evans on Ross Island in the Ross Sea sector of Antarctica. The site was selected for its access to the Ross Ice Shelf, the great floating sheet of ice that provided the route inland towards the South Pole. The small volcanic beach at Cape Evans is one of the few ice-free spots along this coast where ships can anchor and unload.

Ross Island lies in the southern Ross Sea, roughly 3,500 km (2,200 miles) south of New Zealand, making that country the nearest gateway to the region. The island sits within the area known as the Ross Dependency, a sector of Antarctica claimed by New Zealand, and is also within reach of nearby territories such as Australia’s Antarctic Territory to the west.

The History of Scott’s Hut

The story of Scott’s Hut begins with Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s second and final attempt to reach the South Pole. His first expedition had relied on another base, Discovery Hut, but for the 1910–13 Terra Nova Expedition, Scott chose a more northerly site at Cape Evans to reduce the risk of being trapped by sea ice.

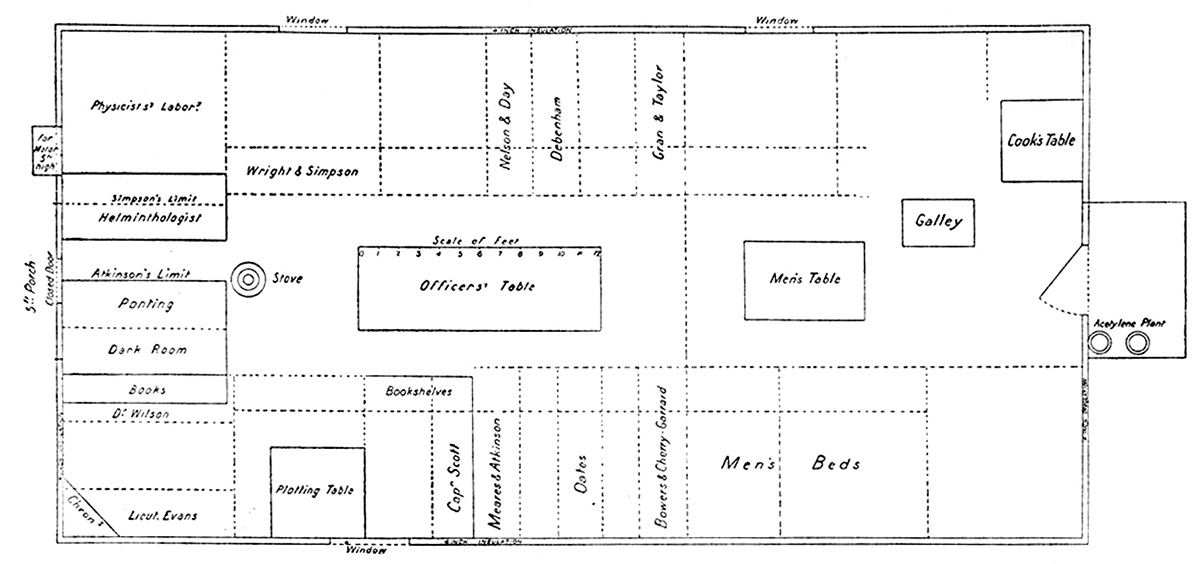

The hut was prefabricated in England by the portable building manufacturer Boulton & Paul. It was transported south aboard the expedition ship, the Terra Nova, and erected by the men on the frozen beach in just a few days in January 1911. Measuring 15 metres (50 feet) by 7.5 metres (25 feet), the structure was advanced for its time. The walls were insulated with quilts of dried seaweed and a carefully designed ventilation system circulated warm air from the stoves. A stable was built alongside to house the 19 Siberian ponies brought for transport, while acetylene gas lamps lit the interior during the long polar winter.

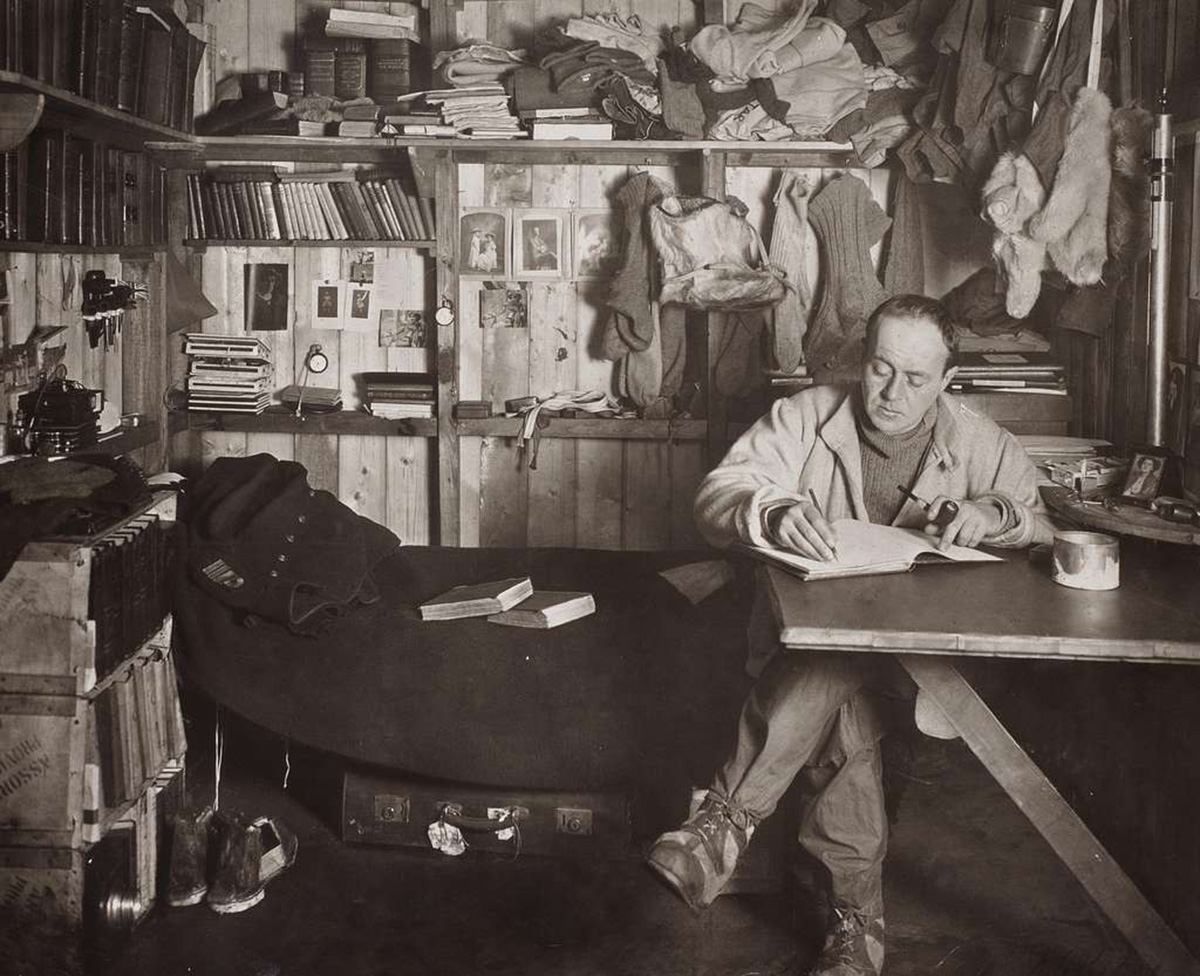

For the winter of 1911, the hut was home to 25 men. It functioned as a living space, scientific laboratory and darkroom with crates of supplies forming partitions between work areas and sleeping quarters. The team conducted extensive research on meteorology, geology, biology and magnetism while preparing for the monumental 2,900 km (1,800 miles) round trip to the South Pole.

On 1 November 1911, Scott and his men set out from Cape Evans. The plan relied on a series of supporting parties to lay depots of food and fuel along the route. These relief parties were vital to the expedition’s success, intended to turn back at predetermined points, leaving a small final party to make the push for the pole.

From the start, the journey was gruelling. The team faced treacherous crevasses, shifting snow, blizzards and sub-zero temperatures that could plunge below −40°C. Travel was slow and exhausting, with sledges hauled by ponies, dogs and the men themselves. Scott’s meticulous planning included scientific observations at each depot but this slowed progress and added to the physical toll.

Meanwhile, news of a rival expedition under Roald Amundsen was reaching Scott through letters and telegrams. The Norwegian explorer had chosen a different route via the Bay of Whales and the Ross Ice Shelf and his team was moving swiftly, benefiting from expert skiing techniques and motorised sledges. The race to the Pole became a pressing concern. Reaching it first would be a source of pride for the British.

By late December, Scott’s teams had laid most of the depots and the final polar party of Scott, Edward Wilson, Henry Bowers, Lawrence Oates and Edgar Evans pushed forward. After weeks of gruelling travel over glaciers, they reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912. There they were confronted with the devastating reality that the Norwegians led by Roald Amundsen had beaten them by five weeks.

The return journey quickly turned into a desperate struggle for survival. Food rations were insufficient, temperatures dropped to extreme lows and the men’s bodies began to fail. Edgar Evans suffered a fall and severe frostbite, dying on 17 February. Lawrence Oates, aware that he was slowing his companions and in agonising pain from frostbite, famously walked out into a blizzard on 17 March, saying, “I am just going outside and may be some time.”

Scott, Wilson and Bowers pressed on but were finally trapped by a relentless blizzard on 19 March, just 18 km (11 miles) from their next supply depot. They died in their tent around 29 March and their frozen bodies were discovered eight months later by a search party.

Why was it Abandoned?

The hut was abandoned by the surviving members of the Terra Nova Expedition in January 1913 once they had completed their scientific work and carried out the search for the missing polar party. Despite the hardships they had endured, the men showed remarkable foresight in how they left their base.

Following a tradition common among explorers of the era, they did not strip the hut bare. Instead, it was carefully stocked with supplies of food, coal and oil in case a future party should find themselves in need. The hut was tidied, secured and locked.

This act of prudence would later prove lifesaving. In 1915, ten members of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Ross Sea Party, a support team for his trans-Antarctic expedition, were stranded at Cape Evans after their ship was torn from its moorings during a blizzard. Forced to survive in extreme conditions for two years, the men took shelter in Scott’s Hut. The provisions left behind by Scott’s team were critical to their survival, providing sustenance, warmth and light during the long, brutal Antarctic winters.

When Shackleton himself finally arrived to rescue the survivors in 1917, he ensured the hut was restored and locked once again, preserving it as both a functional refuge and a historical monument. Scott’s Hut thus stands as a testament not only to the ambition and sacrifice of its original occupants but also to the enduring spirit of preparedness and solidarity that characterised the heroic age of Antarctic exploration.

What is Scott’s Hut like now?

For me, Scott’s Hut is the ultimate time capsule. My research focused on the sheer, haunting reality of the preservation—it is a place where time truly stopped in 1912. I learned exactly what was left behind, frozen in the extreme cold, making the sacrifice of those men profoundly real.

Today, Scott’s Hut is one of the most perfectly preserved historic sites on Earth. After Shackleton’s party left in 1917, the building remained untouched for nearly 40 years, buried beneath snow and ice.

It was rediscovered in 1956 by an American expedition. When they cleared the entrance and stepped inside, they found a remarkable and moving scene. The interior was almost exactly as Shackleton’s men had left it, a time capsule of the heroic age of exploration.

Thanks to the extreme cold and dry polar climate, the preservation is extraordinary. Tins of pemmican, biscuits and jam still sit on the shelves, alongside scientific instruments such as barometers, sextants and microscopes. Clothes hang on hooks, personal journals lie on desks and the table is set as if the men had just stepped outside.

The hut is now managed by the Antarctic Heritage Trust, a New Zealand-based organisation that has undertaken a meticulous conservation project to protect the building and its thousands of artefacts from the slow decay caused by ice, humidity and time.

For me, Scott’s Hut is the ultimate tragedy of human ambition. It’s a silent, frozen witness to courage and heartbreaking loss.

The perfect preservation of the interior is a powerful thing. It allows us to step into a moment frozen in 1912, you feel the presence of the men who lived and worked there.

While access is extremely restricted, I found a link to the incredible Google Street View tour of the interior. It is the best visual proof available of the time capsule I was researching.