If you ride Line 5 of the Paris Métro, you might have noticed a strange flash of light in the dark tunnel between Bastille and Quai de la Rapée. That blur of graffiti and white tiles is Arsenal, a ghost station that has been frozen in time since the day France declared war on Germany in 1939.

I’ve always been fascinated by these ghost stations of Paris. Unlike remote ruins, Arsenal is a secret hiding in plain sight—a time capsule that thousands of commuters rush past every single day, mostly unaware of the history sitting just inches from their window.

Where is Arsenal Station?

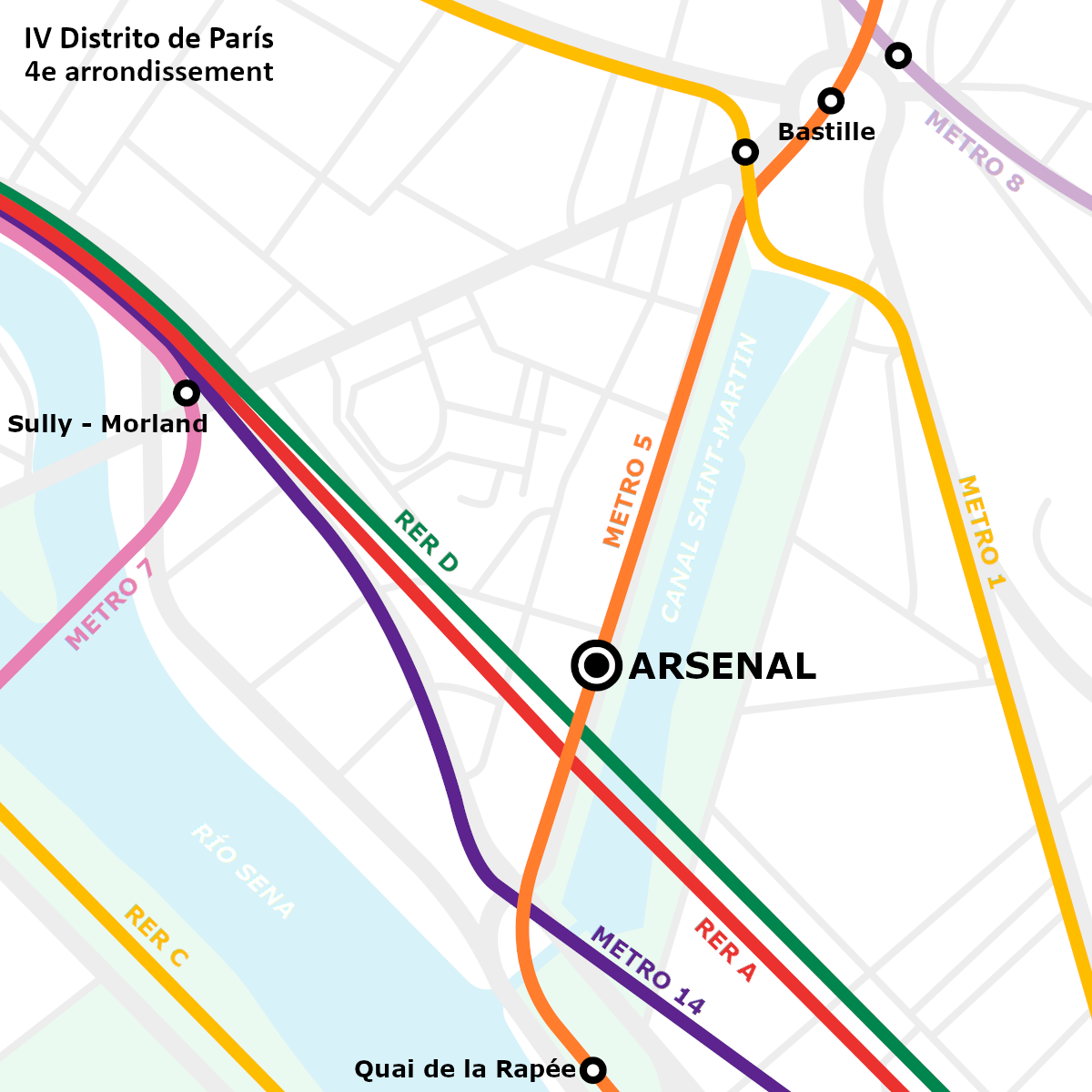

Arsenal station is located in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, on Line 5 of the Paris Métro between the Bastille and Quai de la Rapée stations. Its location is in a historically significant part of the city, named for the Arsenal de Paris, the former royal ammunition and weapons depot that once occupied the area.

The station’s platforms are situated directly beneath the Boulevard Bourdon. Above ground, this places it right on the edge of the Bassin de l’Arsenal, the picturesque boat marina that connects the Canal Saint-Martin to the River Seine. It’s also just a stone’s throw from the famous Place de la Bastille and the modern Opéra Bastille. While trains on Line 5 still pass through the station, its boarded-up street-level entrances offer few clues to the abandoned platforms below.

The History of Arsenal Station

The history of Arsenal station is tied directly to the second wave of the Paris Métro’s rapid expansion. The first line had opened to huge acclaim in 1900 and the city was in a frenzy to build more. The company building the network, the Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris (CMP), was aggressively pushing new lines and Line 5 was a key north-south project. Its construction was a marvel of modern engineering as its route required it to do something spectacular: cross the River Seine.

Building a bridge here presented an enormous challenge. The river navigation authorities forbade the construction of any piers in the river as this was a busy stretch of the Seine and they feared it would impede boat traffic. This forced the Métro’s chief engineer, Fulgence Bienvenüe, and his colleague Louis Biette to devise a radical solution. They designed the Viaduc d’Austerlitz, a colossal 140 metre (460 feet) single-span steel arch, a record-breaking length for any Paris bridge at the time. This massive arch, anchored on huge stone abutments on either bank, allowed the tracks to be suspended high above the water leaving the river entirely clear. The first part of Line 5 opened on 2 June 1906 and just weeks later, on 13 July 1906, the viaduct was complete, allowing trains to make the famous crossing and terminate at a temporary station called Place Mazas (which would later be renamed Quai de la Rapée).

Arsenal station was built as part of the next section, the crucial link that would take the line from Place Mazas north to connect with the rest of the city. This section opened on 17 December 1906, extending the line to Lancry (now Jacques Bonsergent) and adding several new stops including Bastille and Arsenal.

The station’s location was chosen for a clear purpose. It was to serve the residents and workers of the historic Arsenal district. This neighbourhood, named for the former royal ammunition depot, was a dense and bustling part of the 4th arrondissement. The station’s street-level entrance was built right on the Boulevard Bourdon, placing it in a hub of activity between the Place de la Bastille and the Bassin de l’Arsenal, the boat basin connecting the Canal Saint-Martin to the Seine.

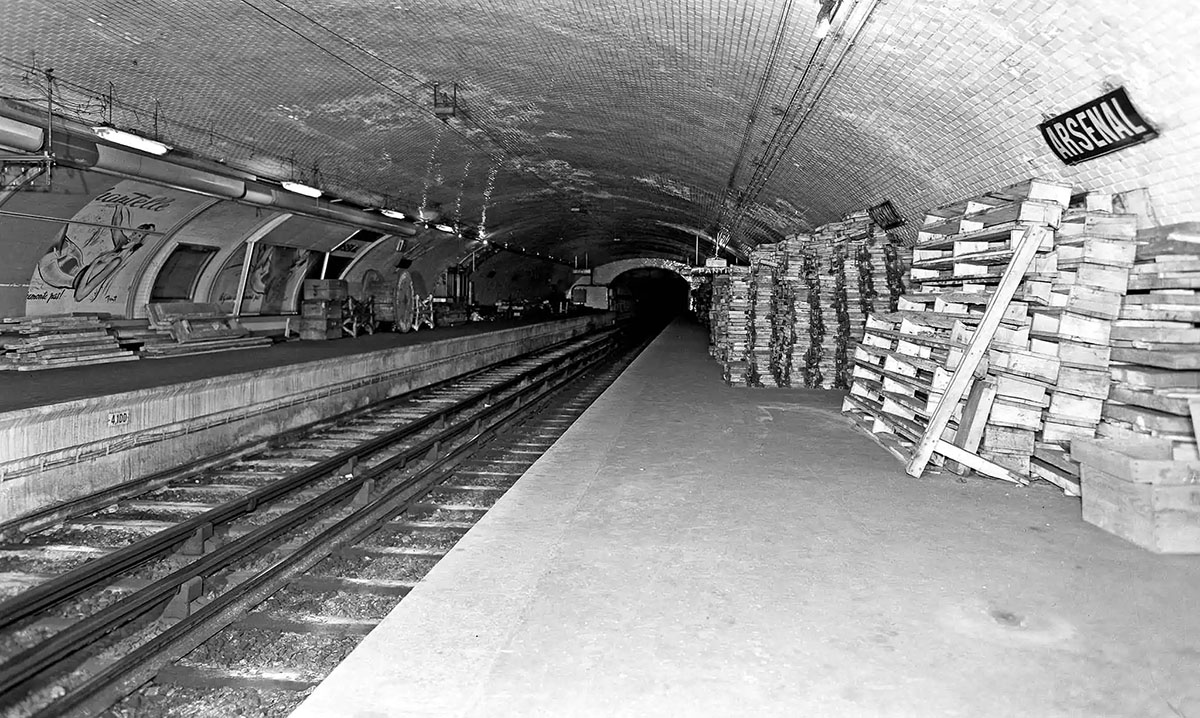

For 33 years, Arsenal was a standard station. Like many others, it would have been a bustling hub of daily Parisian life with its platforms, tiled in the classic white bevelled métro style, filled with commuters, workers and families. Its operational life, however, was to be cut short by global events that would bring its service to an abrupt and, as it turned out, permanent halt.

Why was it Abandoned?

Arsenal station’s operational life came to an abrupt end as a direct consequence of the outbreak of the Second World War. On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. In response, France declared war on 2 September and the French government immediately enacted its plan de mobilisation générale. This order had an instant and profound effect on all aspects of civilian life in Paris, including its vital transport network.

A significant number of the male employees of the Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris (CMP), the precursor to the modern RATP, were conscripted into the French army. This created a severe and immediate staff shortage, making it impossible to operate the entire Métro system. The authorities were forced to make a drastic decision. To conserve limited resources and personnel, only the 85 most essential and busiest stations would remain open. Over two-thirds of the network, including Arsenal, was shut down overnight.

The station was a logical choice for closure. It was not a major interchange and its passenger traffic was relatively low. More importantly, it was located on a section of Line 5 with an unusually high density of stops. Passengers could easily walk just a few hundred metres north to the major hub at Bastille or a similar short distance south to the Quai de la Rapée station. Arsenal, stuck in the middle, was deemed non-essential.

When Paris was liberated in August 1944 and the war in Europe ended the following year, normal life gradually returned to the city. The CMP began the process of reopening the shuttered stations to restore the network to its pre-war capacity. While most stations were eventually put back into service, the transport authority took the opportunity to review the network’s efficiency.

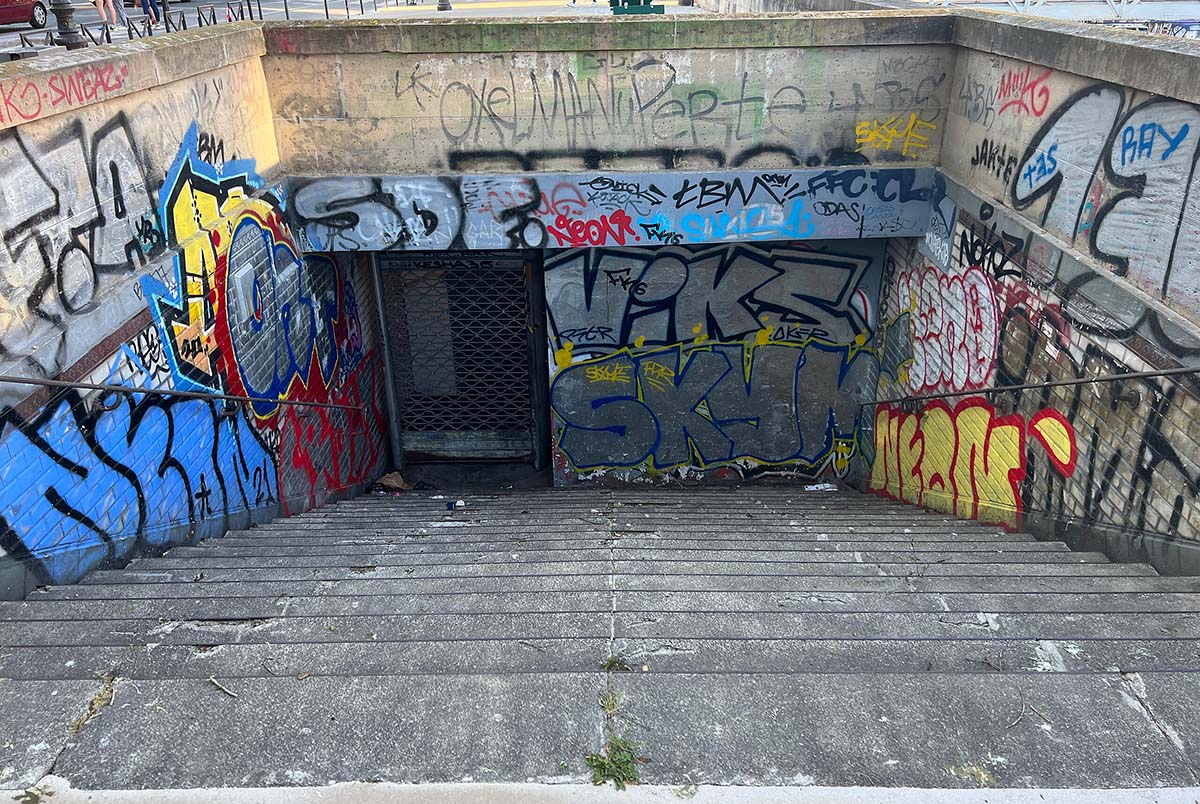

In this post-war assessment, Arsenal’s fate was sealed. The CMP decided that the station was permanently redundant. The operating costs of staffing and maintaining a station so exceptionally close to two others were unjustifiable, especially in a period of post-war austerity. The closure, which was intended to be a temporary wartime measure, was quietly made permanent. The street-level entrances on the Boulevard Bourdon were boarded up, tiled over and eventually cemented. Arsenal station was officially erased from the Métro map, left to be forgotten by the public.

What is Arsenal Station like now?

Today, Arsenal station remains closed to the public, a dark and dusty time capsule right under the city. For decades, it was simply left to decay, its classic white-tiled walls gathering grime as thousands of trains on Line 5 rattled past its empty platforms every day.

It hasn’t been completely useless, though. The station has found some practical use. The Paris transport authority, the RATP, uses the abandoned space as a valuable training centre for its new maintenance staff and for drivers learning the route. It’s also a handy, secure spot to test new network equipment away from the public and its atmospheric, decaying setting has occasionally been opened to film crews.

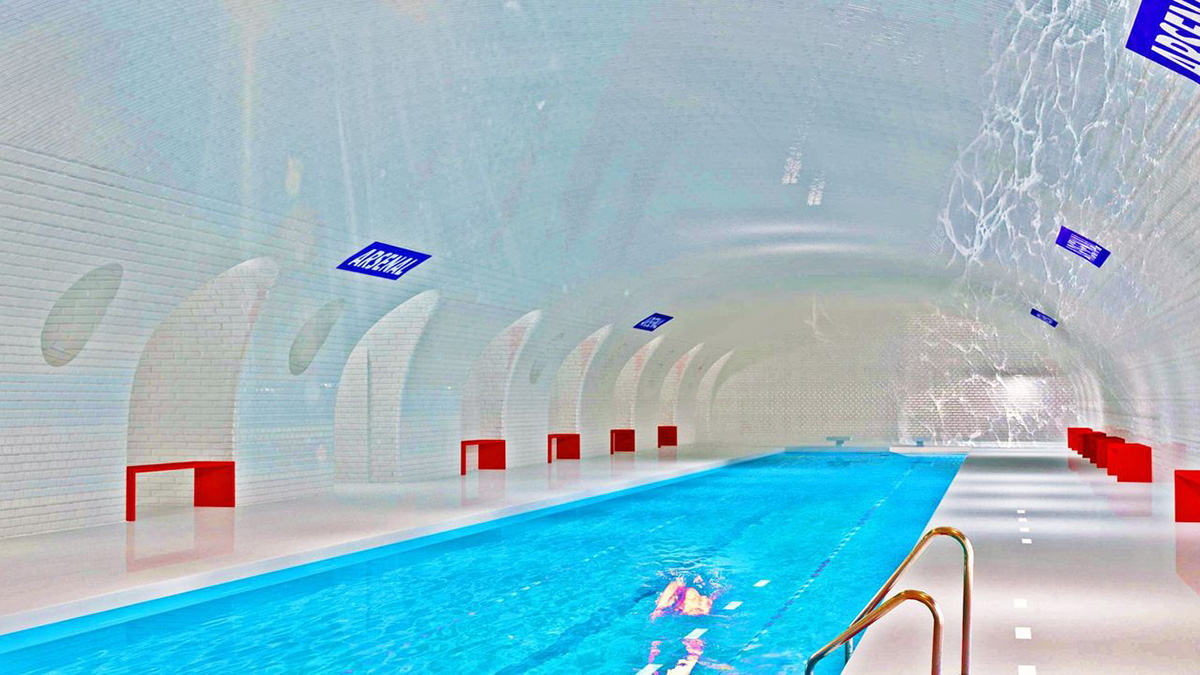

The station’s future became a hot topic in 2014, when mayoral candidate Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet unveiled a series of spectacular architectural proposals to repurpose Paris’s ghost stations. The concept art for Arsenal was the most imaginative, showing the abandoned station transformed into a surreal subterranean swimming pool, a sleek nightclub, a theatre or a modern art gallery.

These ambitious and widely publicized plans captured the public’s imagination, offering a visionary future for the forgotten space. However, there was a catch. The plans were part of an election campaign. When the candidate did not win, the proposals were quietly shelved and have never been acted upon. For now, Arsenal remains as it has been for over 80 years. It’s a silent, empty space in the heart of the Paris underground, a forgotten piece of the city’s history and a tantalizing glimpse of what could be.

For me, Arsenal serves as a constant, silent reminder to every commuter that history is just on the other side of the window. While the ‘swimming pool’ concepts were beautiful, there is something hauntingly perfect about the station staying exactly as it is: a dusty time capsule from 1939 hiding in the dark. It remains the ultimate open secret of the Paris Métro, visible to everyone but accessible to no one.